Why valuation is the most important aspect of growth investing: The example of Netflix

My portfolio is 100% exposed to “growth stocks” with an average of <$1b market cap. Given the current market environment, in which previous high-flyers get cut in half in a matter of days, I believe it is important to reflect on the investment process in order to keep conviction. I don’t want to be the one selling amazon at $7/share in 2002.

Though I do not believe in a value/growth dichotomy — Businesses are worth the present value of their future cash-flows, I do believe in style. After all, there are many reasons to buy a security, and mastering all of them would drive you crazy, so you ought to stick to a proven process. I try to find small cap stocks that will become large cap stocks, and growth is the way these businesses accomplish that.

However, I believe investors often downplay the importance of valuation when investing in these types of stocks. It is true that earnings growth explains most of stock returns over long periods of time, but, there is such a thing as too expensive.

Some investors would disagree with me. Take for example Terry Smith or Brain Stoffel. They pay extremely expensive prices for businesses, and it has arguably worked well for them. However, I would argue that luck is a larger part of those returns than one would expect. Here’s why:

Growth Investing or Interest Rate bet ?

When you buy businesses at 100x Free Cashflow, or 40x Sales, you are making a statement that growth will be fast enough to outpace multiple contraction or that multiples won’t budge. So, are you really making an investment in a business with a variant perception, or are you actually making a bet on future multiple ?

I don’t believe that one can be precise enough in its understanding of a business to have a significant edge on the market when it is already pricing in exceptional amounts of growth with a high probability.

Rather, I would argue that the higher the valuation, the more future multiples matter to your return. And what do future multiples depend upon ? Interest rates.

If the 10-year goes to 15% like in the 70s, unprofitable SaaS stocks that currently trade at 15x Sales will be trading at 3x Sales, even if they are growing at 40% per year. Estimating that a company will be twice as big as the market expects in 5 years, and being right, will not matter if you paid 15x Sales and interest rates go to 15%.

Sure, that’s an extreme argument, but you get the point. When multiples become egregious, return is more sensitive to interest rates than to fundamental business performance. So is it really stock picking ?

People forget how much cheaper stocks were 10 years ago…

As Terry Smith argues in one of his first annual letters, there are many examples of stocks you could have bought at nosebleed valuations and still end up beating the market in the long run. The returns of the stocks converged to the returns of the business. However, they are all exceptional businesses that underwent massive transformation. How could you tell me that buying Microsoft in the late 90s was a good idea because of Azure. You couldn’t.

Really, what has driven the returns of the quality/growth investors over the last decade has been multiple expansion driven by QE and interest rates, the effect of which was felt twice as much in the best businesses. I don’t expect interest rates to go much lower than 0, and I don’t find it logical to pay higher multiple for larger businesses. I don’t buy the argument of paying up for quality/growth, to the same extent as other growth investors do.

It was tough for me as a younger investor to realise that in 2021, no growth stock was worth buying with large enough margin of safety, but I managed to do so by studying the long-term variation in the multiples of high-flyers.

The reason why EPAM, Halma, Amplifon, Sartorius Stedim, Netflix & co had spectacular returns is in part due to multiple expansion, which is unsustainable and even more so as the business grows. EPAM was growing at 25% with 20% operating margins and it IPOed at 15x LTM Earnings in 2012!

By buying these stocks at 3x the multiple they started their runs at, we can’t expect the same returns.

Netflix & the lifecycle of a growth stock

There is more to paying a low multiple than downside protection: Upside potential. One of the books I recommend on the topic is “100 Baggers” by Chris Mayer. He goes into detail about what were the factors the contributed to the outside performance of the stocks that returned 100-to-1. The rules are simple: start small & cheap, and make sure there is double digit earnings growth. Multiple expansion will drive the rest of your returns. Lets take the example of Netflix to understand how this works.

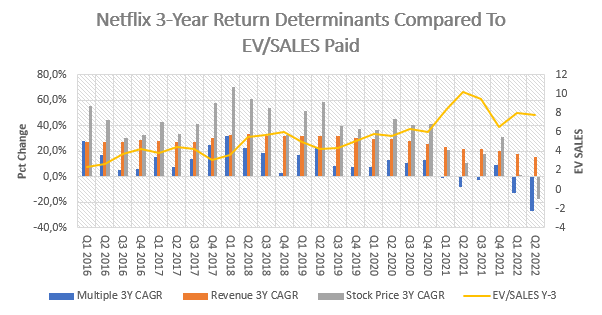

I made a chart below of the quarterly 3 year stock CAGR explained by 3 year multiple expansion CAGR and 3 year sales CAGR. I overlaid the forward P/S paid 3 years prior to prove my point.

Notice how the 3 year revenue CAGR stays flat QoQ for years before slowing from mid-20s to mid-10s. During that period, the P/S paid 3 year prior to each data point rose from 2.4x to a high of 10x.

Why did Netflix’s multiple grow over time, even though its growth rate did pretty much what everyone expected it to do?

It was obvious that once everyone had a subscription, growth would start to decline, and that competition would come to challenge pricing. The multiple should have started off high and declined over time.

Stripping out the effects of interest rates, I think the key factor is that people are willing to overpay for proven business models (even though to be quite frank — Netflix’s business model does have some significant problems). It took a lot of time for Netflix to convince the market that streaming was a great business.

People are risk averse, but they tend to over-emphasise business risks. However, valuation is a risk itself, and should be assessed in tandem with business fundamentals.

Moreover, if one claims to be doing stock picking based on fundamentals, the edge should be in having a variant perception on the business fundamentals ie. assessing the price you pay today to be disconnected with the business performance you expect in the future.

Subsequently, buying businesses that are already proven to be great and obvious to everyone is probably the worst thing you could do because the odds you’ll get are going to be terrible.

Netflix was a great stock pick in the early 2010s, if you had the vision to understand how great their content platform could become and assessed that 2.4x forward sales was giving very good odds. What was tough was understanding the potential of the business, not justifying the valuation.

On the other hand, Netflix was a terrible stock pick in 2018-2021 when the 10x sales valuation was implying that the obvious & frankly unavoidable business risks were not going to materialise. The business fundamentals were clear, it was the valuation that was hard to justify.

Overall, the money is made by buying a low multiple business when you asses that it should be much higher and selling high multiple businesses when it should be much lower. The growth in sales and earnings will act as a multiplier while you wait.

Concluding Thoughts

I want to own great businesses that can grow over long periods of time and sustain high rates of return on capital. I think this strategy is better than fishing for cigar butts because you can buy and hold.

However, if I want to spend my time focusing on the upside, I have to buy stocks that are valued like there is too much downside. That way, I ensure that the risk I am taking is business risk, not valuation risk. That is to me, the essence of fundamental stock picking.

The difficulty comes in trusting your process. You could sell Netflix in Q3 2018 only to see it double in the next 2 years. There is plenty of time to convince yourself that you are wrong.

Hence, it is probably best to be religious about it.